The Signal and the Noise

Nate Silver 2012

- 1. A Catastrophic Failure of Prediction

- 2. Are You Smarter Than A Television Pundit

- 3. All I care about is W’s and L’s

- 4. For Years you’ve been Telling us that Rain is Green

- 5. Desperately Seeking Signal

- 6. How to Drown in Three Feet of Water

- 8. Less and Less and Less Wrong

- 13. What You Don’t Know Can Hurt You

1. A Catastrophic Failure of Prediction

- The ratings agencies had given their AAA rating, normally reserved for a handful of the world's most solvent governments and best-run businesses, to thousands of mortgage-backed securities, financial instruments that allowed investors to bet on the likelihood of someone else defaulting on their home. The ratings issued by these companies are quite explicitly meant to be predictions: estimates of the likelihood that a piece of debt will go into default.

- Standard & Poor's told investors, for instance, that when it rated a particularly complex type of security known as a collateralized debt obligation (CDO) at AAA, there was only a 0.12 percent probability about 1 chance in 850 that it would fail to pay out over the next five years. This supposedly made it as safe as a AAA-rated corporate bond and safer than S&P now assumes U.S Treasury bonds to be.

- In fact, around 28 percent of the AAA-rated CDOs defaulted, according to S&P's internal figures (Some independent estimates are even higher) That means that the actual default rates for CDOs were more than two hundred times higher than S&P had predicted.

- In the instance of CDOs, the ratings agencies had no track record at all: these were new and highly novel securities, and the default rates claimed by S&P were not derived from historical data but instead were assumptions based on a faulty statistical model. Meanwhile, the magnitude of their error was enormous: AAA-rated CDOs were two hundred times more likely to default in practice than they were in theory.

- When you can't state your innocence, proclaim your ignorance: this is often the first line of defense when there is a failed forecast

- The CEO of Moody's, Raymond McDaniel, explicitly told his board that ratings quality was the least important factor driving the company's profits. Instead their equation was simple. The ratings agencies were paid by the issuer of the CDO every time they rated one: the more CDOs, the more profit. A virtually unlimited number of CDOs could be created by combining different types of mortgages or when that got boring, combining different types of CDOs into derivatives of one another. Rarely did the ratings agencies turn down the opportunity to rate one.

- The major difference between a thing that might go wrong and a thing that cannot possibly go wrong is that when a thing that cannot possibly go wrong goes wrong it usually turns out to be impossible to get at or repair

How the Rating Agencies Got it Wrong

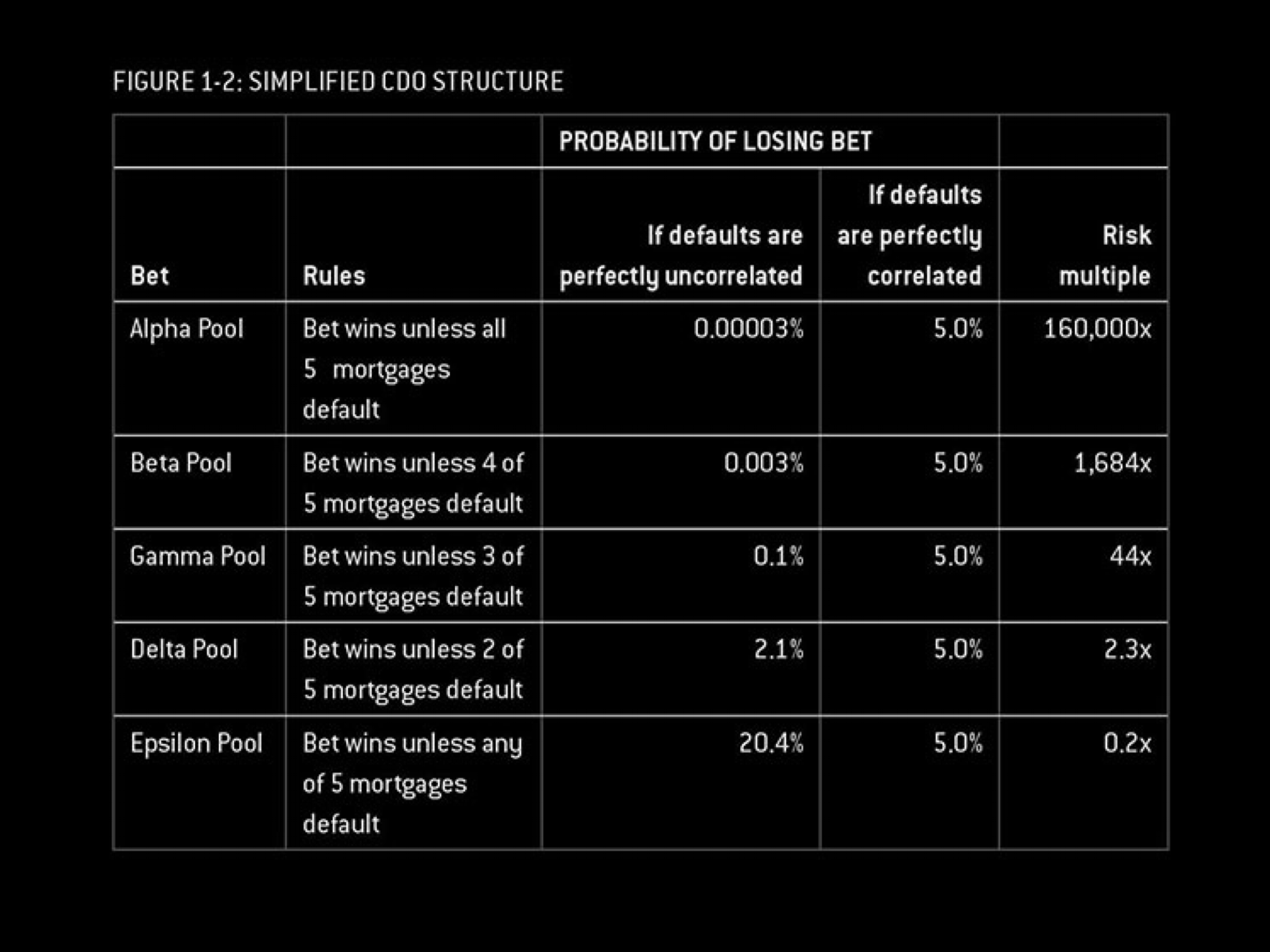

- CDOs are collections of mortgage debt that are broken into different pools, or "tranches” some of which are supposed to be quite risky and others of which are rated as almost completely safe.

- Imagine you have a set of five mortgages, each of which you assume has a 5 percent chance of defaulting. You can create a number of bets based on the status of these mortgages, each of which is progressively more risky. The safest of these bets, what I'll call the Alpha Pool, pays out unless all five of the mortgages default. The riskiest, the Epsilon Pool, leaves you on the hook if any of the five mortgages defaults. Then there are other steps along the way. Why might an investor prefer making a bet on the Epsilon Pool to the Alpha Pool? That's easy-because it will be priced more cheaply to account for the greater risk. But say you're a risk- averse investor, such as a pension fund, and that your bylaws prohibit you from investing in poorly rated securities. If you're going to buy anything, it will be the Alpha Pool, which will assuredly be rated AAA.

- The assumptions and approximations you choose will yield profoundly different answers. If you make the wrong assumptions, your model may be extraordinarily wrong.

- One assumption is that each mortgage is independent of the others. In this scenario, your risks are well diversified: if a carpenter in Cleveland defaults on his mortgage, this will have no bearing on whether a dentist in Denver does.

- The other extreme is to assume that the mortgages, instead of being entirely independent of one another, will all behave exactly alike. That is, either all five mortgages will default or none will Instead of getting five separate rolls of the dice, you're now staking your bet on the outcome of just one. There's a 5 percent chance that you will roll snake eyes and all the mortgages will default making your bet 160,000 times riskier than you had thought originally

- Suppose that there is some common factor for all homeowners like a massive housing bubble that has caused home prices to rise by 80 percent without any tangible improvement in the fundamentals

- It wasn't just a possibility that their estimates of default risk could be 50 percent too low: they might just as easily have underestimated it by 500 percent or 5,000 percent. In practice, defaults were two hundred times more likely than the ratings agencies claimed, meaning that their model was off by a mere 20,000 percent

- Risk, as first articulated by the economist Frank H. Knight in 1921, is something that you can put a price on.

- Say that you'll win a poker hand unless your opponent draws to an inside straight: the chances of that happening are exactly 1 chance in 11. This is risk. It is not pleasant when you take a "bad beat" in poker, but at least you know the odds of it and can account for it ahead of time. In the long run, you'll make a profit from your opponents making desperate draws with insufficient odds.

- Uncertainty, on the other hand, is risk that is hard to measure.

- You might have some vague awareness of the demons lurking out there. You might even be acutely concerned about them. But you have no real idea how many of them there are or when they might strike. Your back-of-the envelope estimate might be off by a factor of 100 or by a factor of 1,000; there is no good way to know. This is uncertainty. Risk greases the wheels of a free-market economy; uncertainty grinds them to a halt

Act 1: The Housing Bubble

- After adjusting for inflation, a $10,000 investment made in a home in 1896 would be worth just $10,600 in 1996. The rate of return had been less in a century than the stock market typically produces in a single year.

- Instead, the housing boom had been artificially enhanced through speculators looking to flip homes and through ever more dubious loans to ever less creditworthy consumers. The 2000s were associated with record-low rates of savings: barely above 1 percent in some years. But a mortgage was easier to obtain than ever. Prices had become untethered from supply and demand, as lenders brokers, and the ratings agencies-all of whom profited in one way or another from every home sale strove to keep the party going.

- A survey commissioned by Case and Schiller in 2003 found that homeowners expected their properties to appreciate at a rate of about 13 percent per year. In practice, over that one-hundred-year period from 1896 through 1996 to which I referred earlier, sale prices of houses had increased by just 6 percent total after inflation, or about 0.06 percent annually.

Act 2: Leverage, Leverage, Leverage

-

leverage - borrowing money to make more money

-

Lehman Brothers, in 2007, had a leverage ratio of about 33 to 1 meaning that it had about $1 in capital for every $33 in financial positions that it held. This meant that if there was just a 3 to 4 percent decline in the value of its portfolio, Lehman Brothers would have negative equity and would potentially face bankruptcy.

The Market for Lemons

"If you're in a market and someone's trying to sell you something which you don't understand," George Akerlof told me "you should think that they're selling you a lemon."

- Akerlof demonstrated that in a market plagued by asymmetries of information, the quality of goods will decrease and the market will come to be dominated by crooked sellers and gullible or desperate buyers.

- Imagine that a stranger walked up to you on the street and asked if you were interested in buying his used car. He showed you the Blue Book value but was not willing to let you take a test-drive. Wouldn't you be a little suspicious? The core problem in this case is that the stranger knows much more about the car, its repair history, its mileage, than you do.

- Sensible buyers will avoid transacting in a market like this one at any price. It is a case of uncertainty trumping risk. You know that you'd need a discount to buy from him-but it's hard to know how much exactly it ought to be. And the lower the man is willing to go on the price, the more convinced you may become that the offer is too good to be true. There may be no such thing as a fair price. But now imagine that the stranger selling you the car has someone else to vouch for him. Someone who seems credible and trustworthy, a close friend of yours, or someone with whom you have done business previously. Now you might reconsider. This is the role that the ratings agencies played. They vouched for mortgage-backed securities with lots of AAA ratings and helped to enable a market for them that might not otherwise have existed.

- credit default swaps -investments that pay you out in the event of a default and which therefore provide the primary means of insurance against one they were only able to reduce their exposure by about 20 percent &lIt was too little and too late, and Lehman went bankrupt on September 14, 2008

Intermission: Fear is the New Greed

- If Lehman Brothers was no longer able to pay out on the losing bets that it had made, this meant that somebody else suddenly had a huge hole in his portfolio. Their problems, in turn, might affect yet other companies, with the effects cascading throughout the financial system

- negative feedback - as prices go up, sales go down, good for economy

- positive feedback - as prices go up, sales go up

- fear and greed - Some investors have little appetite for risk and some have plenty, but their preferences balance out: if the price of a stock goes down because a company's financial position deteriorates, the fearful investor sells his shares to a greedy one who is hoping to bottom-feed

- Greed and fear are volatile quantities, however, and the balance can get out of whack. When there is an excess of greed in the system, there is a bubble. When there is an excess of fear, there is a panic.

What the Forecasting Failures Had in Common

There were at least four major failures of prediction that accompanied the financial crisis.

- The housing bubble can be thought of as a poor prediction. Homeowners and investors thought that rising prices implied that home values would continue to rise, when in fact history suggested this made them prone to decline.

- There was a failure on the part of the ratings agencies, as well as by banks like Lehman Brothers, to understand how risky mortgage-backed securities were. Contrary to the assertions they made before Congress, the problem was not that the ratings agencies failed to see the housing bubble. Instead, their forecasting models were full of faulty assumptions and false confidence about the risk that a collapse in housing prices might present.

- There was a widespread failure to anticipate how a housing crisis could trigger a global financial crisis. It had resulted from the high degree of leverage in the market, with $50 in side bets staked on every $1 that an American was willing to invest in a new home.

- Finally, in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, there was a failure to predict the scope of the economic problems that it might create. Economists and policy makers did not heed Reinhart and Rogoff's finding that financial crises typically produce very deep and long-lasting recessions

There is a common thread among these failures of prediction. In each case, as people evaluated the data, they ignored a key piece of context:

- The confidence that homeowners had about housing prices may have stemmed from the fact that there had not been a substantial decline in U.S. housing prices in the recent past. However, there had never before been such a widespread increase in U.S. housing prices like the one that preceded the collapse.

- The confidence that the banks had in Moody's and S&P's ability to rate mortgage-backed securities may have been based on the fact that the agencies had generally performed competently in rating other types of financial assets. However, the ratings agencies had never before rated securities as novel and complex as credit default options.

- The confidence that economists had in the ability of the financial system to withstand a housing crisis may have arisen because housing price fluctuations had generally not had large effects on the financial system in the past. However, the financial system had probably never been so highly leveraged, and it had certainly never made so many side bets on housing before.

- The confidence that policy makers had in the ability of the economy to recuperate quickly from the financial crisis may have come from their experience of recent recessions, most of which had been associated with rapid, "V-shaped" recoveries. However, those recessions had not been associated with financial crises, and financial crises are different.

- Out-of-sample - unseen data not accounted for in models or forecasts

- often neglected because out-of-sample data includes cases that will make the model seem less accurate

- personal and professional incentives discourage use of out-of-sample data

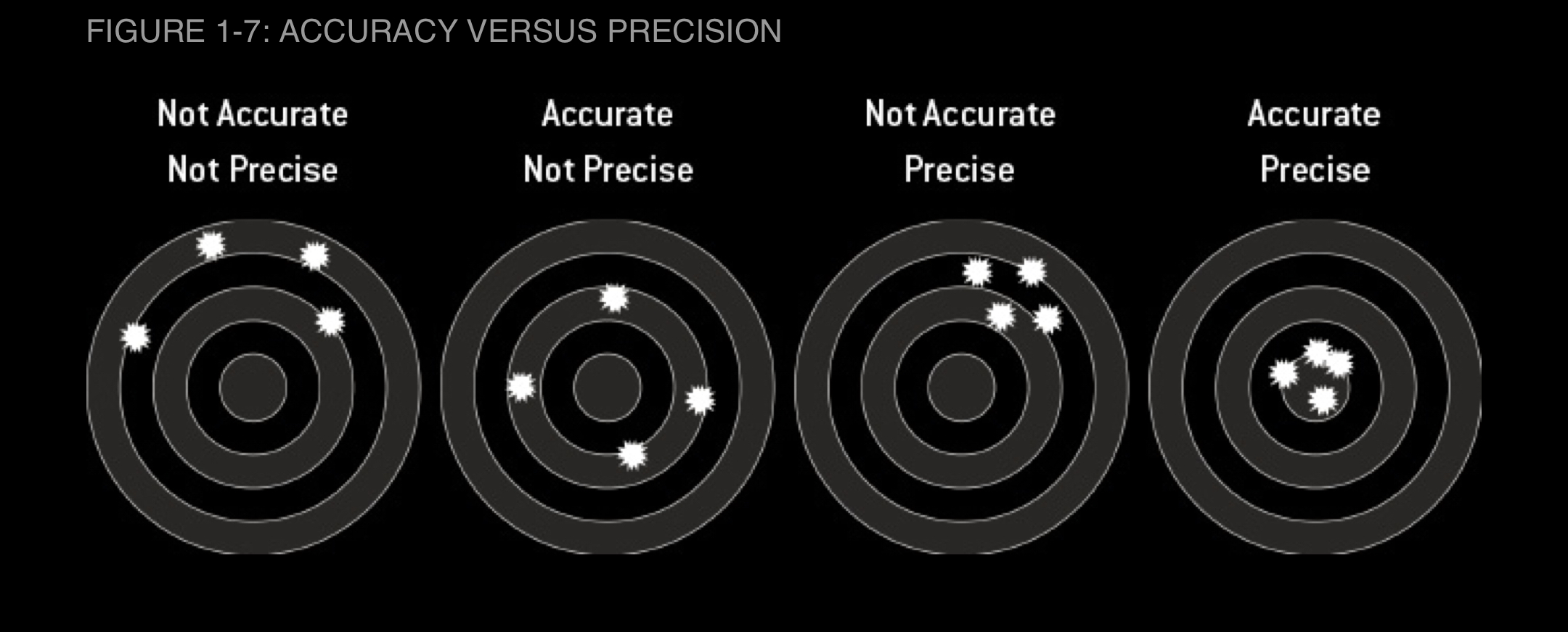

- don’t mistake precision for accuracy

2. Are You Smarter Than A Television Pundit

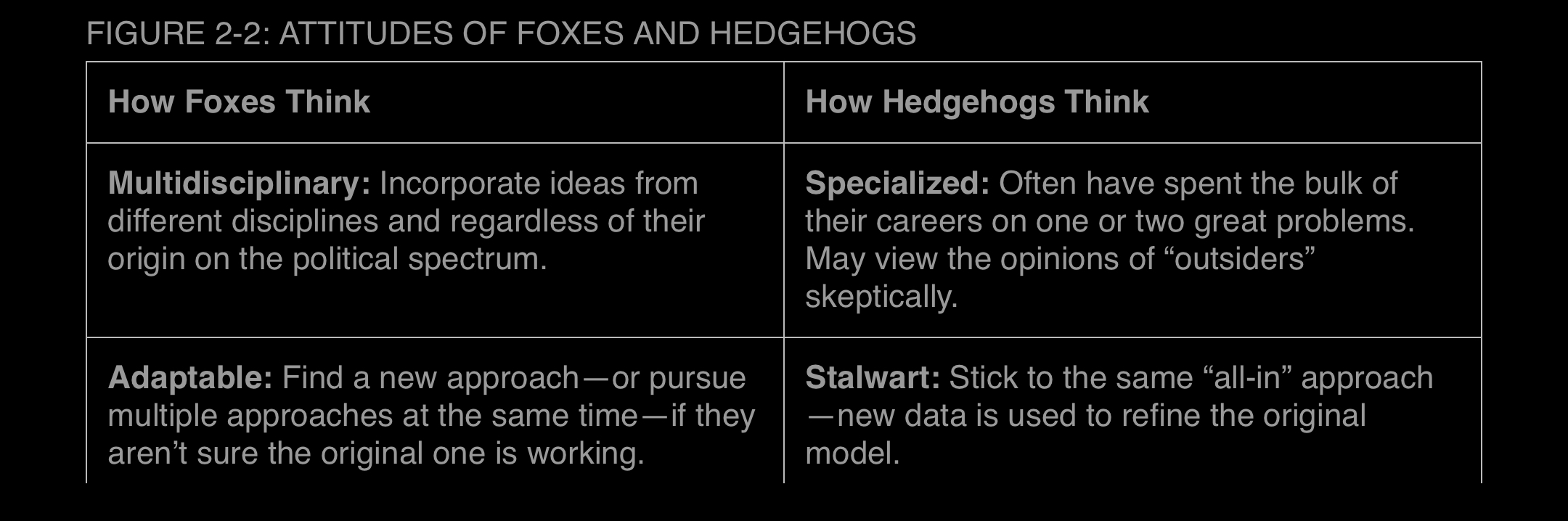

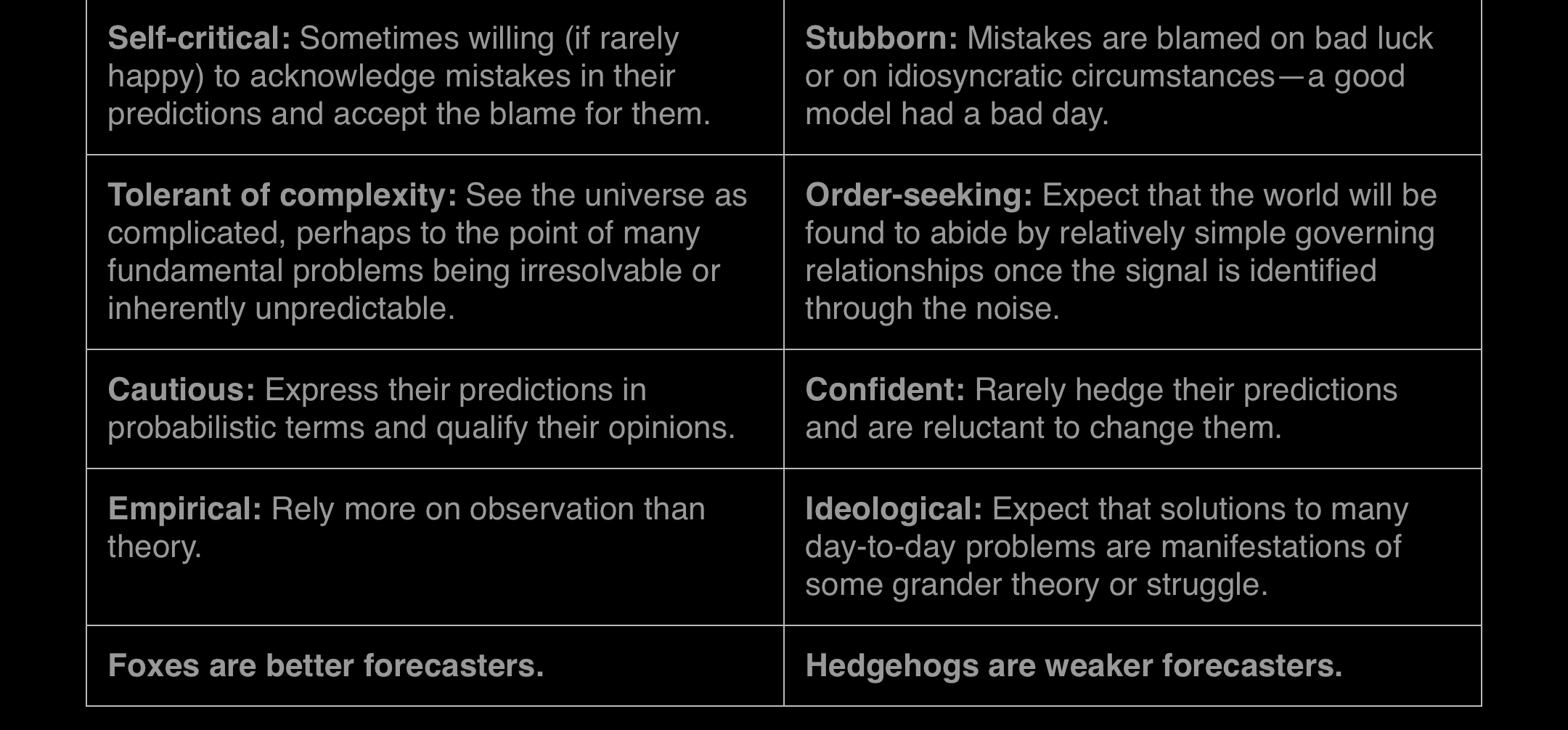

- Hedgehogs and Foxes are type A personalities who believe in Big Ideas-in governing principles about the world that behave as though they were physical laws and undergird virtually every interaction in society. Think Karl Marx and class struggle, or Sigmund Freud and the unconscious. Or Malcolm Gladwell and the "tipping point.

- Foxes, on the other hand, are scrappy creatures who believe in a plethora of little ideas and in taking a multitude of approaches toward a problem. They tend to be more tolerant of nuance, uncertainty, complexity, and dissenting opinion. If hedgehogs are hunters, always looking out for the big kill, then foxes are gatherers.

FiveThirtyEight Principles

- Think Probabilistically

- articulate a range of possible outcomes

- Today’s Forecast is the First Forecast of the Rest of Your Life

- make the best possible forecast with the data available

- update forecast when new data is available

- Look for Consensus

- aggregate forecasts are often more accurate than individual ones

3. All I care about is W’s and L’s

A good baseball projection system must accomplish three basic tasks:

- Account for the context of a player's statistics

- Separate out skill from luck

- Understand how a player's performance evolves as he ages- curve

4. For Years you’ve been Telling us that Rain is Green

- Determinism - all events are determined by previously existing causes

- Deterministic system - a system in which no randomness is involved in the development of future states of the system. A deterministic model will thus always produce the same output from a given starting condition or initial state

- Laplace’s Demon - Given perfect knowledge of present conditions ("all positions of all items of which nature is composed"), and perfect knowledge of the laws that govern the universe ("all forces that set nature in motion"), we ought to be able to make perfect predictions ("the future just like the past would be present"). The movement of every particle in the universe should be as predictable as that of the balls on a billiard table. Human beings might not be up to the task, Laplace conceded. But if we were smart enough (and if we had fast enough computers) we could predict the weather and everything else and we would find that nature itself is perfect.

- Perfect predictions are impossible if the universe itself is random

- weather happens at a molecular (rather than an atomic) level

Chaos Theory

- The systems are dynamic, meaning that the behavior of the system at one point in time influences its behavior in the future

- outputs at one stage of the process become inputs for the next

- And they are nonlinear, meaning they abide by exponential rather than additive relationships.

- small changes in input can produce large difference in the output

- dynamic systems are hard to predict

- The NWS keeps two different sets of books: one that shows how well the computers are doing by themselves and another that accounts for how much value the humans are contributing. According to the agency's statistics, humans improve the accuracy of precipitation forecasts by about 25 percent over the computer guidance alone, and temperature forecasts by about 10 percent. Moreover, according to Hoke, these ratios have been relatively constant over time: as much progress as the computers have made

- In 1940, the chance of an American being killed by lightning in a given year was about 1 in 400,000. Today it’s just 1 in 11,000,00 or 30 times less likely

- one sign that you have made a good forecast is that you are equally at peace with however things turn out not all of which is within your immediate control. But there is always room to ask yourself what objectives you had in mind when you made your decision.

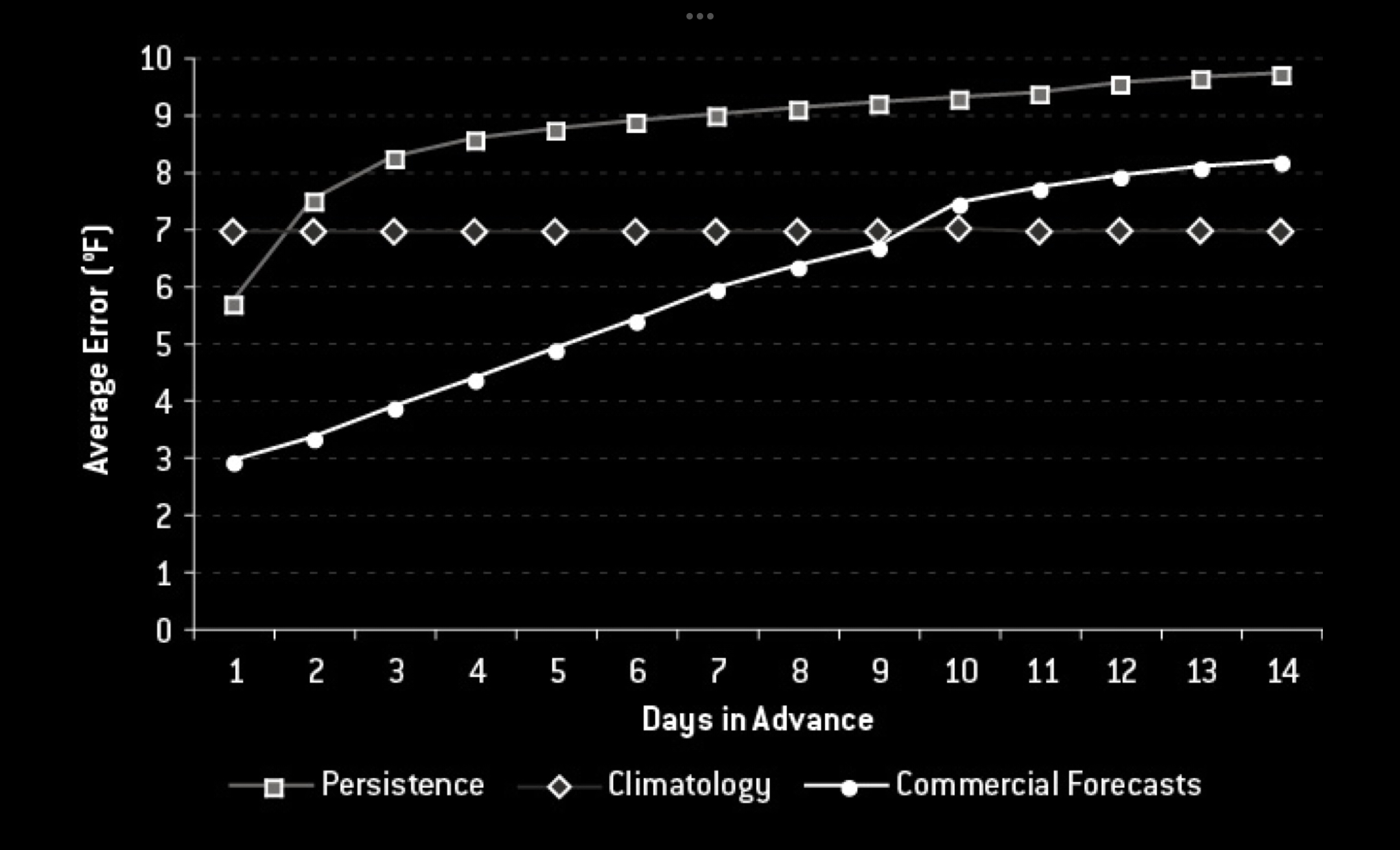

There are two basic tests that any weather forecast must pass to demonstrate its merit:

- It must do better than what meteorologists call persistence: the assumption that the weather will be the same tomorrow (and the next day) as it was today.

- It must also beat climatology, the long-term historical average of conditions on a particular date in a particular area.

- the further out in time models go, the less accurate they turn out to be (figure 4-6) Forecasts made eight days in advance, for example, demonstrate almost no skill; they beat persistence but are barely better than climatology. And at intervals of nine or more days in advance, the professional forecasts were actually a bit worse than climatology.

- After a little more than a week, chaos theory completely takes over, and the dynamic memory of the atmosphere erases itself

- calibration - out of all the times you said there was a chance an event would happen, how often did this event happen

5. Desperately Seeking Signal

- a prediction is a definitive and specific statement about when and where an earthquake will strike: a major earthquake will hit Kyoto, Japan on June 28

- whereas a forecast is a probabilistic statement, usually over a longer time scale: there is a 60 percent chance of an earthquake in Southern California over the next thirty years

- Something that obeys this distribution(power-law) has a highly useful property: you can forecast the number of large-scale events from the number of small-scale ones, or vice versa. In the case of earthquakes, it turns out that for every increase of one point in magnitude, an earthquake becomes about ten times less frequent. So, for example, magnitude 6 earthquake occur ten times more frequently than magnitude 7’s, and one hundred times more often than magnitude 8’s.

- predicting the past is an oxymoron

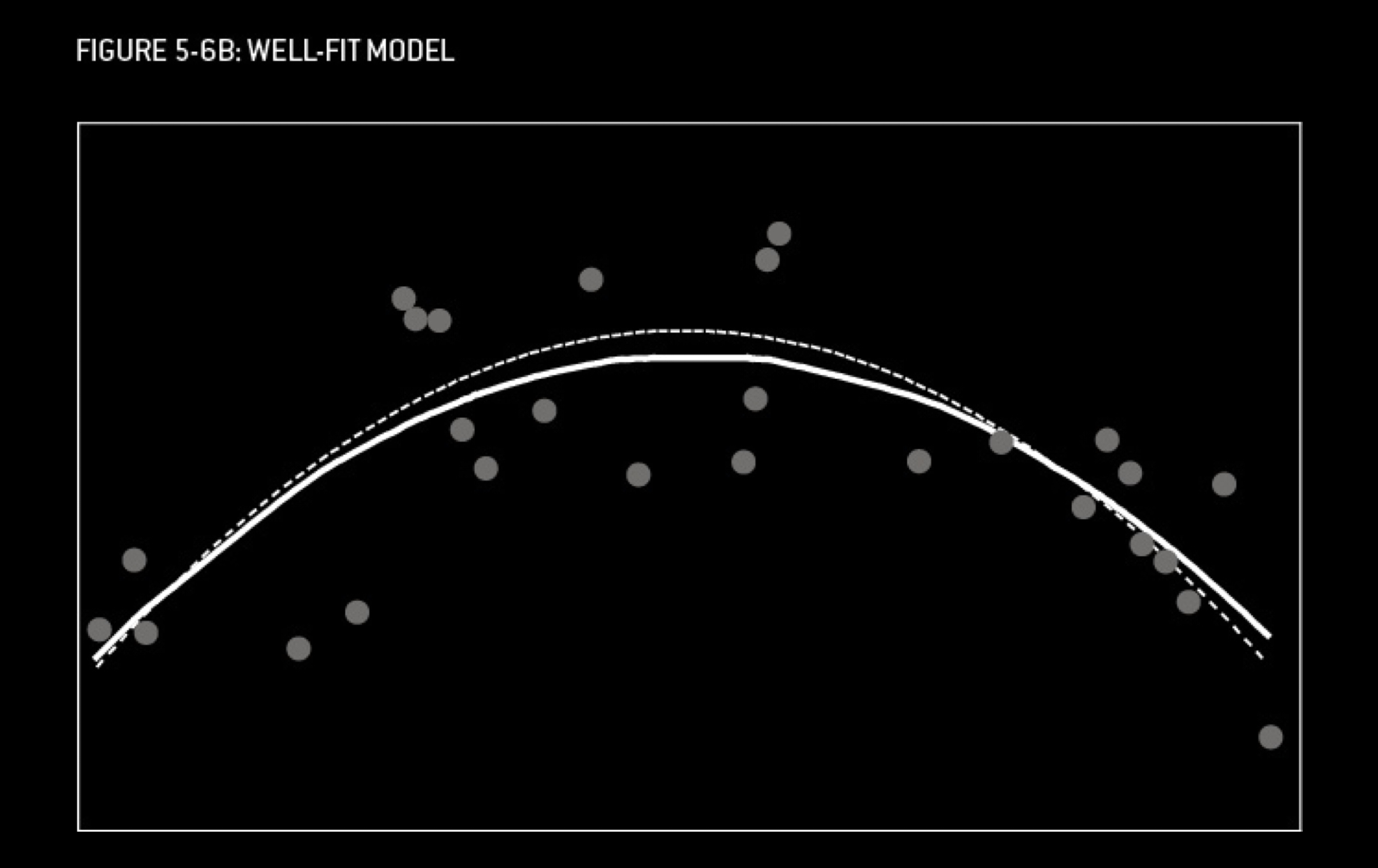

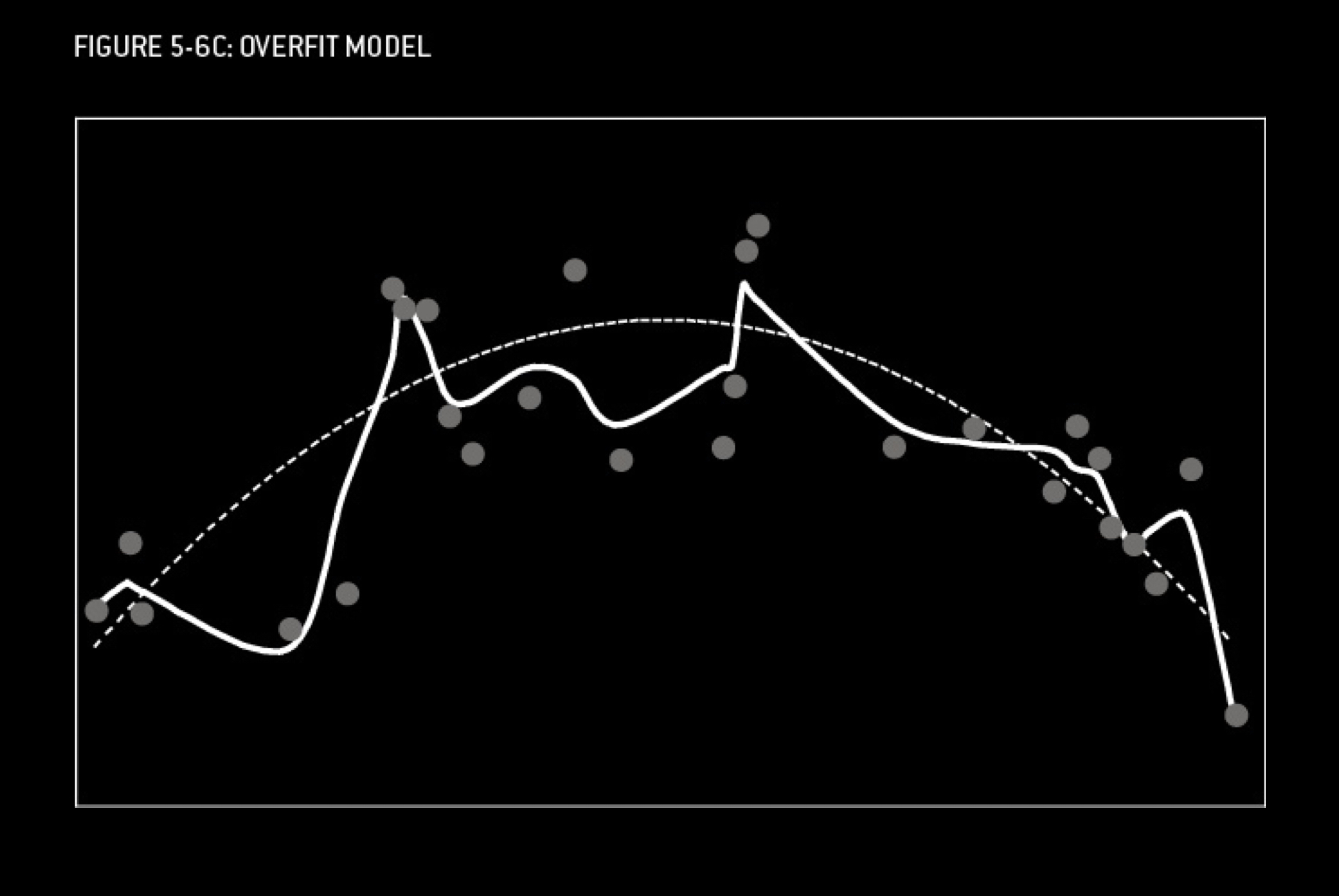

- In statistics, the name given to the act of mistaking noise for signal is overfitting

- You’ve given me an overly specific solution to a general problem. This is overfitting, and it leads to worse predictions.

- there are lots of reasons why we may be prone to overfitting the model, one is that the overfit model will score better according to the most of the statistical tests that forecasters use. A commonly uses test is to measure how much of the variability in the data is accounted for by our model. According to this test, the overfit model explains 85 percent of the variance making it “better” than the properly fit one which explains 56 percent. But the overfit model scores those extra points in essence by cheating — by fitting noise rather than signal. It actually does a much worse job of explaining the real world.

- Overfitting represents a double whammy: it makes our model look better on paper but perform worse in the real world

- We may, without even realizing it, work backward to generate persuasive-sounding theories that rationalize them, and these will often fool our friends and colleagues as well as ourselves

- “In science, we seek to balance curiosity with skepticism”

6. How to Drown in Three Feet of Water

- rational bias - the less reputation you have, the less you have to lose by taking a big risk when you make a prediction

8. Less and Less and Less Wrong

- Bayes’s theorem is concerned with conditional probability. That is, it tells us the probability that a theory of hypothesis is true if some event has happened

- probability of event as a condition of hypothesis being true

- probability of event as a condition of hypothesis being false

- prior probability

- You should work to reduce your biases, but to say you have none is a sign that you have to many

- to say “Here’s where I’m coming from” is a way to operate in good faith and to recognize that you perceive through a subjective filter

- The idea behind frequentism is that uncertainty in a statistical problem results exclusively from collecting data among just a sample of the population rather than the whole population. This makes the most sense in the context of something like a political poll. A survey in California might sample 800 people rather than 8 million who will vote, producing what’s known as sampling error.

13. What You Don’t Know Can Hurt You

- signal - an indication of the underlying truth behind a statistical or predictive problem

- noise - random patterns that might easily be mistaken for signals

- No Israeli politician would say outright that he tolerates small-scale terrorism, but that’s essentially what the country does. It tolerates it because the alternative — having everyone be paralyzed by fear — is incapacitating and in line with the terrorists’ goals

- small-scale terrorism is treated more like crime than an existential threat